Rating of

4/4

Hell or High Water- Carnivorous Couch Review

CarnivorousCouch - wrote on 03/03/17

It feels appropriate that, of all the great scenes in David Mackenzie’s Hell or High Water, the one probably most fated to become iconic involves a woman telling her customers that her restaurant only serves T-bone steaks and baked potatoes. Hell or High Water is the best example in recent memory of what one might call a steak-and-potatoes movie. There is a certain breed of film that has a kind of generally appealing and unfussy quality to it. It’s the kind of film that leads people of many different stripes to smile, reflect fondly and say, “Well that was just a very good movie.” Movies of this sort are not typically known for being conspicuously artistic nor for being the least bit cerebral. Like the T-bone steak in that West Texas saloon, the steak-and-potatoes movie is relatively unadorned, a movie to be appreciated largely on its own surface pleasures. The simple steak-and-potatoes movie tends to be broadly accessible, energetically paced and frequently quotable. These are all qualities that Hell or High Water shares. The curious thing about my great affection for Hell or High Water is that I am not, by my nature, a steak-and-potatoes kind of viewer. I am particularly fond of challenging films, and I am just as happy sitting down to watch brutal Romanian abortion drama 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days as I am watching Finding Nemo. With most steak-and-potatoes movies, I too often find something in their consensus-building palatability that robs them of vitality or personality. They can sometimes be lacking in idiosyncrasy. I have recently run into this issue with films like The Martian, The King’s Speech, and particularly Argo. These films wear their relative simplicity like a badge of honor, and that’s not necessarily wrong of them. Simplicity can be a virtue. The problem is, as much as I generally quite like two of those films (and technically like Argo), I found their simple populism to be what held them back from getting anywhere near greatness. Their lack of artistic flourish only seemed to throw light onto the deficiencies in their storytelling or character development or thematic depth (or all three in the case of Argo). To make a steak-and-potatoes film is to put the focus entirely on the meat of your story, and that Spartan approach really only pays off if you have very high quality meat. This is where those three films suffer and where Hell or High Water succeeds. Hell or High Water has the distinction of being a downright delicious slab of plain, old storytelling, and that is why it has the honor of being the one and only “simply great” film in my Top 20 this year.

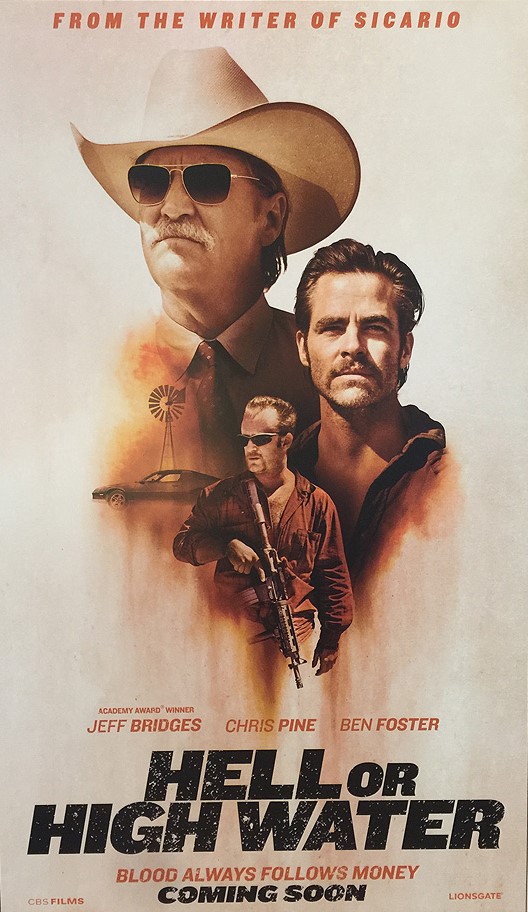

To be fair, my own personal preferences for showier work almost got the better of me when I saw the film in the summer of 2016. I walked out of Hell or High Water having enjoyed the film deeply and recognizing a certain resonance in its depiction of post-recession America. I knew immediately, in my heart of hearts, that I had just seen a very, very fine film. But it was quite a simple film and this gave me pause. I started to have doubts that it would leave me with much to chew on. The story of the film is that of two Texan brothers, Toby (Chris Pine) and Tanner (Ben Foster), who set out to rob the bank that is foreclosing on their family home. If they do not have a certain sum of money wired to Texas Midlands Bank by the end of the week, they will lose both the property and the right to collect the vast amounts of oil that have recently been discovered underneath it. Tanner is a recently paroled criminal with experience in robbing banks. He also did time early in his life when he shot their abusive father. It is Toby, however, a veteran with a clean record, who has masterminded the scheme and who has a plan for how they can get away with it. They will only hit the bank that has victimized them and they will only steal smaller sums from tellers’ drawers, which means all the money they receive will be untraceable. As the two hit more banks, they are followed by a retiring Texas Ranger named Marcus (played with keen, crotchety charm by Jeff Bridges) and his younger partner, a half-Mexican half-Native American man named Alberto (a great, dry Gil Birmingham). The film’s main story is about Toby and Tanner, as they rob, launder their money at a Native American casino, and make plans to put the property into a protected trust for Toby’s sons, but it is also the story of the relationship between the two rangers. Marcus toes the line between puckish and prejudiced as he continually cracks jokes about Alberto’s heritage. Alberto alternatingly puts up with him and tosses out his own barbs, mostly about the fact that Marcus is too old to still be out chasing the law enforcement high that he is so clearly afraid to give up. Hell or High Water is about both action and conversation; robberies and moments of stillness between both sets of men. And, without underlining the point too emphatically, it is also about the state of a country with deep class divisions and increasingly scant opportunities for the upward mobility so central to its origin story. At the end of the film, as Toby and Marcus meet on his front porch for a fateful conversation, Toby explains why someone like him might rob a bank. Being poor, he says is “like a disease, passed down from generation to generation. But not my boys, not anymore.” At the end of my first viewing, I joined the theater in applause. Once again, I knew right away that Hell or High Water was a terrific and topical film. And, as someone who sues on behalf of foreclosure victims for a living, I certainly empathized with and rooted for its fallible soulful protagonists. Still, name-checking a social problem and having a comprehensive, insightful discussion on that problem are two separate things, and I wondered if Hell or High Water was more than an exciting, engaging hyperlink to an important issue. Maybe it was more a heist film in the 2008 mortgage crisis’ clothing than a genuine, seething expose of our financial institutions. It took me multiple conversations with friends to realize what a deceptively great and nuanced piece of work Hell or High Water is.

The first sign of the film’s sneaky greatness was its quotability. This is never a guarantee of quality. I continue to be something of a holdout on Napoleon Dynamite and I would never in a million years deny that it is chock full of memorable lines. But the fact I could so easily quote Hell or High Water after watching it only one time made me start to look back at its script. Most steak-and-potatoes crowd-pleasers are not nearly this well-written. There I was on a Friday night, standing on my porch with a beer, and I started chuckling to myself about that scene with the waitress and the T-bone steaks. Then my friend laughed and said, “Only assholes drink Mr. Pibb.” And before I knew it, I was quipping back, “So drink up, asshole.” And this kept happening over the weeks. Any time talk turned to Hell or High Water, it would end in an exchange of sharp, funny quotes. I came to gradually see what a firecracker of a script this is, and not just for the one-liners and quips either. The writing is also often downright pretty in a way that both suits and subverts its tough, masculine tone. Toby’s recurring fascination with Comanches as the “lords of the Plains”. Alberto’s beautifully bitter soliloquy about how the banks’ avarice and blindness to human suffering are echoes of the same greed and cruelty visited upon his Native American ancestors. The way Marcus points to a bank teller and muses that he “looks like a man who could foreclose on a house”. Writer Taylor Sheridan keeps the action and the beats of the plot succinct and straightforward, but he also knows that simplicity is not the same thing as drabness. Simple lines can also be poetic. It is even the challenge that many great poets have set for themselves: to wring beauty and epiphany out of the least possible number of words. Look at Tanner’s solo robbery. It’s a short scene. Tanner just wants to the teller to display all the increments of cash in her drawer. But Sheridan injects even this brief bit of business with welcome color. “Fives. Tens. Twenties. Fan ‘em out like a deck of cards.” Money and cards, crime and gambling. All manifestations of the dream of some easy escape from poverty. All there in this five second snippet of a robbery. Fittingly, for a film soundtracked with country music and Nick Cave’s evocative Western score, the dialogue in Hell or High Water rings with the bruised, blunt beauty of a great country song.

As line after line came rushing back to my memory, scenes came back too. And as I began to recall those scenes, it dawned on me that Hell or High Water is one of those works of art with no filler. It is the kind of film that ends one great scene so it can move on to the next great scene. I cannot name a moment from it that I would call inessential. Each moment has a purpose and its placement in the narrative leads organically to another moment which also has a strong sense of purpose. The final product is a film that knows exactly what it means to do and does it. I do not normally require such efficiency from films I love. Some of my favorite films sprawl and malinger and I am content just to bask in them for as long as they want to have me. This approach would not have fit Hell or High Water. Its clean, propulsive momentum is the secret ingredient that turns it from a standard issue bank robbery tale into something terse, stirring, and almost elemental. Have you ever picked up a great album, perhaps by The Beatles or Marvin Gaye or The Rolling Stones, and realized that every last song on it is a timeless classic? Better yet, to choose an artist who almost nobody dislikes, think about Michael Jackson. Pick up “Thriller”, turn it over, and look at the tracklist. You realize you’re looking not only looking at a great album, but one that never once stops being great; not even for a moment to catch its breath. Hell or High Water feels a lot like that. If I ever read its DVD menu, I imagine it will feel like reading a no-filler tracklist. “Wow,” I’ll say, “that great casino scene leads right into that scene where Marcus and Alberto are watching that sleazy television preacher and theorizing about God in a seedy motel room. And that leads right into the scene where the new attorney they’ve hired as an executor knows they’re bank robbers and can barely contain his glee. And after that is the T-bone steak scene, which is just perfect.”

So you have subtly poetic writing, great scenes, and an almost total absence of any fatty downtime, which means that this story about desperate bank robbers in economically depressed Texas is strangely kind of a giddy joy to watch. It throws you in the back of a getaway car and speeds like a madman for 104 minutes that feel like less than an hour. And the thing that happened on my second viewing, when I knew how thoroughly I was about to enjoy myself, is that I gave myself over to it completely. And in that content, undistracted state, another layer of the film’s greatness started to come back to me. I remembered that I love these characters. Just as with the dialogue, Sheridan’s script creates characters that are extremely well-defined but too vivid and unique to ever become mere archetypes. Ben Foster takes the role of a shit-kicking jailbird and imbues him with a mischievous intelligence that transcends the bold lines of the standard ne’er-do-well. In the first robbery, Tanner snaps at a teller for calling him stupid. Tanner is reckless, impulsive, and prone to some very bad decisions, such as improvising a robbery alone while his brother is eating in a diner next door, but not stupid. Some of his decisions are terrible and ill-advised, but the character also has poetry in his outlaw country soul. Chris Pine does the best work of his career as Toby. He is the level-headed one with the clean criminal record, but he is neither a saint nor immune to poor choices and violent outbursts. When two young men in a lime-green muscle car try to start a fight with Tanner (who is utterly willing to goad them on) Toby shows up and slams one of their heads into a car door. The brothers have their individual, opposing personalities, but they each share shades of the other as well. Meanwhile, Jeff Bridges takes the part of the irreverent, culturally insensitive ranger and give him shades of neediness and fear of the uncertain future. He becomes a more impish but no less haunted version of Tommy Lee Jones’ sheriff in No Country For Old Men. And Gil Birmingham creates a nuanced portrait of a Hispanic and Native American lawman who has learned to navigate through an intolerant world. He is shrewd, determined, and resourceful. In a year full of great performances by non-white actors, any list without Gil Birmingham on it would be incomplete.

And all around the main four characters are memorable, beautifully specific entrances and exits by smaller characters. Tiny, detailed jewels of acting to complement the larger gems. Most are by actors I have never seen before. That sardonic waitress in the steakhouse. The Comanche man who confronts Tanner at the poker table. The eager citizen who drives Marcus to his final confrontation with Tanner. The kindly single mother who waits on Toby at the diner and who repays his generous tip with her own act of generosity. How can I say this without seeming to contradict everything I’ve said before? Hell or High Water really is a simple film, but for a film mostly just about two bank robbers and the lawmen pursuing them, it has a wonderfully rich sense of detail. And so much of that is a credit to those tiny characters who show up for a single scene and, one by one, help give a face to the broader financial struggle always in the background of the film. These are the human beings who have to live in this world besieged by robber barons and crooked lenders and they lend a larger sense of gravitas to Tanner and Toby’s private war with Texas Midlands Bank. The film also derives a wealth of detail from the locations it breathlessly races through. The film paints a world of oil fields and debt relief billboards. Tire stores and churches and casinos. And, of course, banks. Hell or High Water only tells a small segment of the story of the acquiring and the acquired in modern America, but the monuments to their existence are everywhere.

Hell or High Water is that rare example of a film that finds poetry and grace in its directness. It manages to be both humble and overflowing with flavor. It is a bit of a paradox, but this is the same film that can both stand with the year’s funniest comedies and have a scene that calls back to Captain Phillips in its realistic depiction of post-violence trauma. What at first seems slight eventually turns out to actually just be marvelously condensed; a vibrant world of compelling characters, relatable struggles, and playful language all tightly ground down into a delectable nugget of crime fiction. Seeing Hell or High Water reminds me that my real issue with most steak-and-potatoes films is that the meat of their stories is never high-grade enough to justify how little they do artistically. A top quality steak only needs a pinch of salt, but the meat of your average no-frills crowdpleaser is rarely anything like a top quality steak. At the risk of exhausting this food analogy, Hell or High Water can afford to be direct and thematically simple and still feel fulfilling because the meat of its story and its characters are delicious all by themselves. When the basics are in place the way they are here, you don’t need the A-1 sauce of extraneous directorial touches or overly self-consciously cerebral writing to make it work. I feel satisfied calling Hell or High Water one of the year’s twenty best films. It’s about time I had a simple film on my year-end list. As if making a funny, elegiac, humane, tersely poetic, quietly political, endlessly quotable bank robber flick was actually simple.