Rating of

4/4

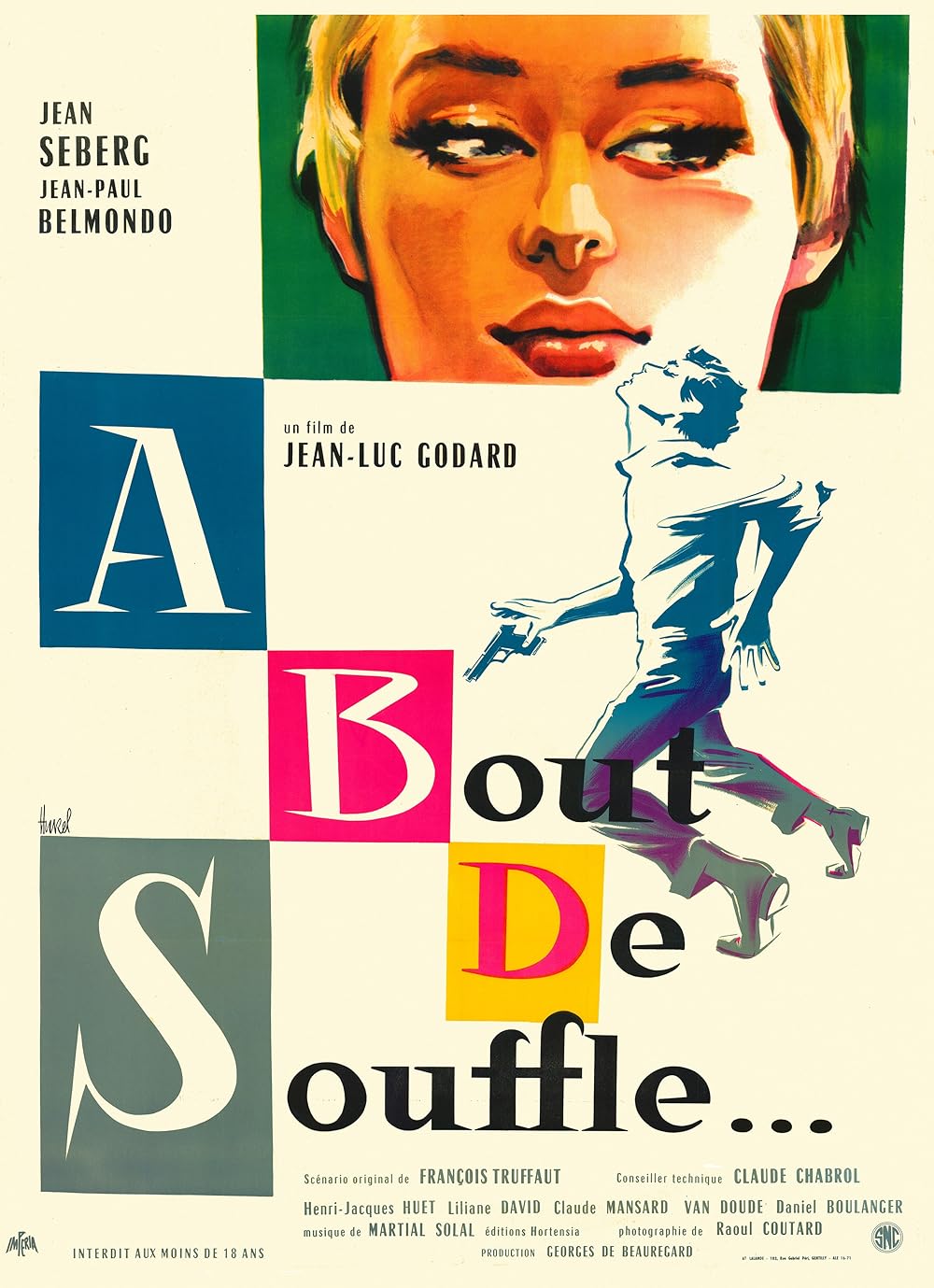

Breathless

SteelCity99 - wrote on 04/25/18

The title of "Breathless" is pretty self explanatory. The French New Wave had barely begun approximately five years ago, and Jean-Luc Godard was audacious and adventurous enough to portray his cinematic style in its most complete way in his first film. À Bout de Souffle contains every technical aspect, every charming detail and every single auteur frame that distinguished Godard as a revolutionary of cinema. At the end of terms, it may be referential cinema. However, its quirkiness and extreme improvisatory feeling allowed the art of filmmaking to be capable of taking elements that clearly distinguished the pop culture of the time, referencing famous stars and personalities and applying a unique signature. The cinematic movement that allowed France to be recognized as a stylish and gorgeously stereotypical country through its films was subject to an extreme boost precisely with À Bout de Souffle, a film that celebrates the unexpected outcomes of life, the animal and irrational impulse that love may cause (thus erasing any possible logical consequence) and exalting the human condition in the most romantic way possible, not necessarily resorting to an exaggerated portrayal of romance and melodrama, but relying on the effect that incongruent, yet realistic reactions of the film protagonists may ultimately cause on an audience.

The film opens with an impulsive and careless sociopath named Michel Poiccard, a man as passionate as love itself who loves to imitate the characteristic facial gestures of the famous actor Humphrey Bogart. He makes a living stealing cars and reselling them to Paris. After stealing a car and murdering the motorcycle policeman who had been pursuing him without any premeditation of his actions whatsoever, he flees to Paris and asks for money to an old girlfriend of his. However, he soon renews his relationship with a beautiful American girl. Her name is Patricia Franchini, an aspiring journalist who will be under the constant flattering and unprofessional romantic behavior of Michel despite his face being on the media while being chased by the authorities. On his plan of performing a getaway to Italy, the lives of the protagonists will soon be facing an unpredictable series of inevitable events. Director Jean-Luc Godard won a Silver Berlin Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival of 1960. He was also nominated for a Golden Berlin Bear, losing it against César Fernández Ardavín for his film El Lazarillo de Tormes (1959), a rather ingenious Spanish comedy.

Rumors ensued regarding Godard shooting the film without a previously elaborated script. Although this statement was not precisely truthful, the extreme improvisatory ability of Godard of writing scenes in the morning and shooting them the same day may be a factor that can be immediately contrasted and even compared with how life is never premeditated. Life is portrayed as a game and as a series of incidents that may surpass its old interest and usual importance if a daily routine is constantly broken. The film challenges the stereotypes of modern culture, urging them to test their audacity. Everything is subject of mockery and Godard does never hesitate to depict the people who constantly try to follow them, especially the ones that are principally disseminated through movies and mass media, and to make these people to question how honest and original this kind of attitudes really are regarding their particular personalities. The performance of Jean-Paul Belmondo is the source of this vision, a man who is subject to the influence of the popularity imposed by the mass media thanks to the motivations of financial aims. Moreover, he applies a personality that does not entirely belong to him and lets it take over his conscience, consciously. Opposite poles attract; therefore, a lovable and patient femme fatale was required. Although her highly Americanized appearance may seem to hide a tender and weak female personality beneath her persona, she ironically is a stereotype herself. A conceited criminal meeting a lover of artistic values strongly promises a cinematic explosion. It is like if the story by the already acclaimed director François Truffaut (Les Quatre Cents Coups [1959], Tirez sur le Pianiste [1960]) with the aid of the poetical screenplay by Jean-Luc Godard introduced reality with the fantastic realm of cinema. It provides the sensation to the viewer of suddenly being sucked by the screen and fulfill his/her dream of becoming (or living with) the characters that one may particularly love or be a fan of. This makes À Bout de Souffle easy to admire.

Godard scatters layers and stylish shots and unites them into a single fluent scene. This is where the editing plays its magical role, constantly jumping from scene to scene and cutting them with no remorse. This highlights life's subjectivity, an element beautified by the extraordinary musical score composed by Martial Solal. Although its repetitiveness is a noticeable feature, it effectively works to provide a fast-paced rhythm to the film, like if prophetically celebrating an upcoming sexual liberation and an anarchic lifestyle. Moral standards are broken and the sexual content is very present, a possible fact that may have caused the banning of the film for almost four years. His constant use of editing and changes in the use of music seemingly takes a break with a wonderful cinematography that gives life to shots that last nearly three minutes. The joyous and sexy feeling À Bout de Souffle provides the 75% of the time is partially interrupted by sequences that evoke romance and tranquility, a daring transition for the early days of a director. The film does not deviate from its nonstop emotiveness and its positive pretentiousness, giving away as a final outcome a scandalous commentary towards conservative values and supposedly unnecessary censorship.

It is the audacity of the film and its attempt of staying away from a high possibility of intentional banality what makes À Bout de Souffle the definitive manifesto of the French New Wave. Making homage to the genres that made American cinema and culture famous, it is a very important piece of filmmaking that ambitiously works as a testament towards the beauty of life and the negative implications of the human impulses. Godard was careful enough to add an internalized purpose of scandal into the film. Therefore, the sensations the movie caused worldwide are nowadays considered as the result of a landmark film. Long shots contrasted with discontinuity, a supposedly impossible romance, a man looking under the skirt of a woman and enjoying the consequent slap in the face, the unintentionally intentional comedy, a blasphemous depiction of the concept "popularity", the attack against conservatism and the aid that it shows towards liberal ideas with an anarchic touch, this is much more than the definition of "cool". It is a sexual liberation, cinematically speaking, and the director's best film, a task that very few filmmakers have achieved during the history of cinema.

100/100